An Appetite for Darkness

Understanding evil, confronting the Jungian shadow, and becoming whole

I’m a fan of psychological thrillers and I’ve always thought, “isn’t is strange that I love making myself feel nervous, scared, or haunted?” Paradoxically, I think the voluntarily confrontation of evil is actually what makes me feel safe.

Understanding evil

A while back, I tweeted about why I like the intelligent villain trope. In classical mythology and fairytales, the good is represented by the light and the evil, by darkness. Mufasa has a golden mane and sits proudly in the sun while Scar has a dark mane and dwells in the graveyard with his hyenas (i.e. animals that feed on rot). The reason why the intelligent villain is so unique is because it does not conform to the expected archetype or psychological profile of good vs. evil:

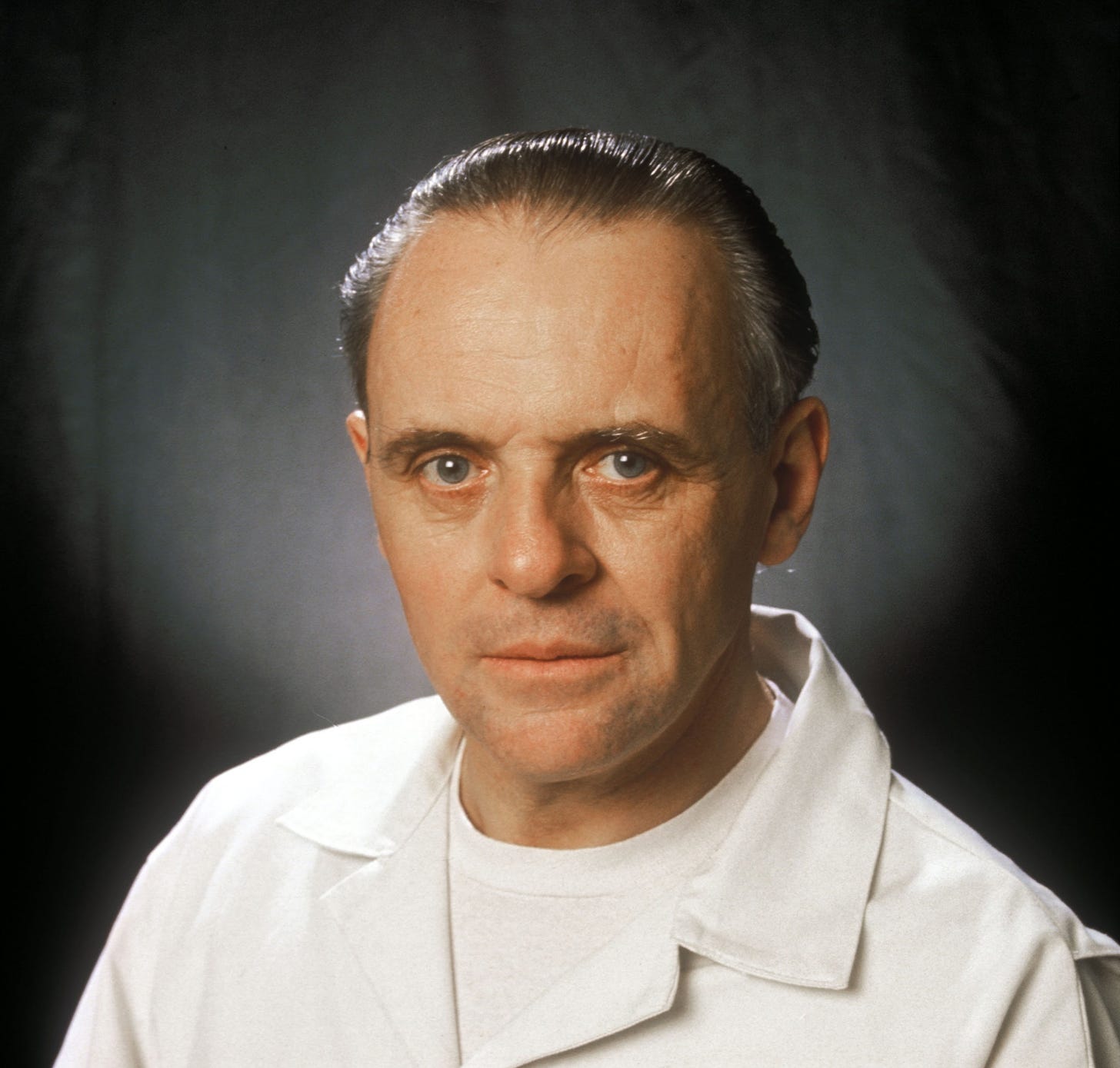

The intelligent villain is disciplined (Hannibal Lecter), educated (Dr. Octopus), and principled (Voldemort). He likes beauty, classical music, and the fine arts (Alex DeLarge). He’s an obsessive perfectionist who’s does evil in the name of altruism or justice (Thanos). He’s loyal to his own purpose, mission-driven, ambitious, and faithful (even if it’s to all the wrong gods). In a way, aren’t these traits positive?

What this trope tells us about good and evil is that they do not exist in separation. In fact, evil lies right next to virtue:

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties—but right through every human heart…to do evil a human must first believe that what he’s doing is good.”

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

If good and evil do not exist in separation, then there’s one more sobering realization: You and I, average Joes, are capable of evil as much as we are capable of good. As Joker would say, “all it takes is one bad day to reduce the sanest man to lunacy.”

We are undoubtedly fascinated by evil—why else do we watch dramatic representations of serial killers (true crime or fiction), assassins, spies, psychopaths, and kingpins of the world of crime? Why else do we voluntarily frighten and disgust ourselves with horror films? Deep down inside, it’s more than lecherous curiosity; it’s an understanding of the moral structure we all exist within when judging good versus evil. This understanding is crucial because it shows us what is above us and what is below us—we look up to the saints and down at the demons. We share a universal benchmark when measuring right against wrong.

The Jungian shadow

“The shadow goes by many familiar names: the disowned self, the lower self, the dark twin or brother in bible and myth, the double, repressed self, alter ego, id. When we come face-to-face with our darker side, we use metaphors to describe these shadow encounters: meeting our demons, wrestling with the devil, descent to the underworld, dark night of the soul, midlife crisis.”

— Connie Zweig

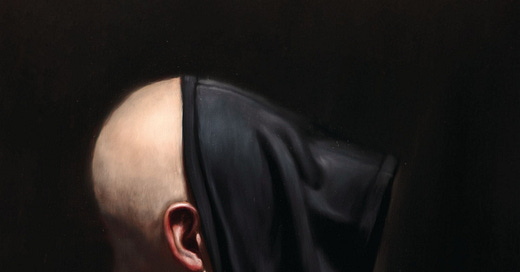

The shadow describes the hidden portion of our personality which, through experience, is banished to the unconscious. We hide it because it makes us shameful or fearful, or maybe because it makes us loathe ourselves. It is our ugly side.

If I were to ask you, “do you think you’re a good person?” your knee-jerk reaction would probably be something like, “yes, I think so/I’ve stayed relatively out of trouble my whole life/I know right from wrong.” No one thinks they’re the villain in their own story. Its’s harder to see the faults in yourself than in others, because we hide our negative qualities not only from others but from ourselves. That, by definition, is what a shadow is. It’s what is blocked from the light, and to shine a light on something means to bring revelation upon it. A shadow is the negative space of light, it is what is neglected by revelation and ignored by the eye of the mind.

It doesn’t take a criminal record to be labeled as someone who has done something seriously wrong—I’m not referring to slitherers who’ve managed to escape legal outcomes, I’m referring to the general proclivity for evil that resides in every human heart. Not everyone is a criminal, but everyone has the capacity to become one.

I’d take it one step further: It is necessary to be someone who is capable of evil. In other words, it is necessary to reach into your own shadow and figure out what dwells there. Why?

In an older lecture, Dr. Jordan Peterson said:

“If you're harmless you're not virtuous, you're just harmless, you're like a rabbit; a rabbit isn't virtuous, it just can't do anything except get eaten! A harmless man is not a good man. A good man is a very, very dangerous man who has that under voluntary control.”

To understand evil means to be able to protect yourself from it. For example, if you encounter someone with malevolent intentions, they have the power to hurt you in ways that you precisely do not know why or how. If you don’t understand evil (or are unwilling to), you leave yourself susceptible to its claws.

And I think this is the appeal of thrillers. The observation of evil modeled by fictional characters is like looking into the depth of human depravity to witness just how bad things can get, so we know how great we can be in our battle against it.

Gold in the dark

My favorite depiction of the shadow self is in the film Horrible Bosses when Nick imagines himself hurling his psychopathic boss through a window after being ridiculed and cheated out of a promotion he was teased about. The scene is wonderfully shot because you don’t realize that Nick is fantasizing until he snaps out of it—not unlike how we daydream alternate realities in our own lives. Most importantly, we cheer Nick on in his attempt to murder his boss without hesitation. We hate his boss as much as he does, we take delight in the demise of a disgusting narcissist.

In his daydream, Nick acts the opposite of who he really is. Real-Nick is meek, submissive, and afraid of getting in trouble, whereas fantasy-Nick is aggressive, sailor-mouthed, domineering, and brutishly assertive in getting what he wants.

We don’t know why Nick is the way he is, but we know for sure that he would be better off if he stood up for himself more. We wish we could see Nick earn what he deserves. We wish we could see him realize what a pushover he is. Imagine how great Nick’s life would be if he understood evil and armored himself earlier in his career—he wouldn’t be working for Harken, maybe he’d even be ahead of Harken by now. While throwing someone out of a window is not the most helpful solution (although it may be the most cathartic), there is something to be said about aggression. When placed correctly and used with control, aggression is a good thing.

Well-managed aggression can be what gets you the upper hand in a critical negotiation. It can be what secures you a parking spot at the mall during peak shopping hours. In a more serious case, it can be the difference between life and death in a hostile situation if you’re out late at night. Aggression, when mismanaged, becomes an obvious engine of harm.

To seize the gold in your shadow is to recognize how dangerous you can be, manage the danger, and grow into what you are afraid to become. Virtue is not merely being able to do good—it’s being able to confront and control evil. As Jung said, “Good does not become better by being exaggerated, but worse, and a small evil becomes a big one through being disregarded and repressed…the most terrifying thing in the world is to accept oneself completely.”

Integrating the shadow into a whole

The shadow isn’t always what is evil, it’s simply what is opposite from the side that is shown to the world. For example, there’s an uncanny pattern about serial killers loving animals. Anthony Casso loved animals but killed 36 people. Sammy Gravano was an underboss of the Gambino crime family yet owned a farm for his cherished horses. Roy DeMeo killed 100 people but would stop mowing his lawn to save frogs. Whitey Bulger was known for feeding stray cats and pampering poodles before he was known for taking 19 lives. People who commit atrocious acts of unspeakable violence are often those who, when asked about after they’re caught, would be described by neighbors as someone who wouldn’t hurt a fly. Many such cases.

It’s just that this is uncommon. Most of us display our virtues and hide our dark side.

The tree in the mythological story of human origin gives a dual product. Whenever we pluck a fruit of creativity, our other hand plucks a fruit of destruction. We would love to have creativity without destruction, but that’s not possible. It is called “the Tree of Knowledge” because recognizing good or evil requires knowing what both are in contrast to one another. You can not distinguish good without knowing evil, and vice versa.

St. Augustine, in The City of God, once said, “To act is to sin.” To create is to destroy at the same time. We can not cast a light without simultaneously casting a shadow. Our resistance to this idea is high because we don’t want to admit to anyone, including ourselves, that we could be a menace.

In Hinduism, Brahma, the god of creation, and Shiva, the god of destruction, sit on the two sides of Vishnu, the ultimate protector of the world, who keeps the opposites together. Vishnu is said to watch the world by balancing good and evil.

I find this to be one of Jung’s greatest insights: the ego and the shadow ultimately come from the same source and balance each other exactly. To make light is to make shadow—one cannot exist without the other.

Robert Johnson, a client of Jung, once said:

“To own one’s own shadow is to reach a holy place—an inner centre—not attainable in any other way. To fail this is to fail one’s own sainthood and to miss the purpose of life.”

After all, it is not perfection that we should strive for, but wholeness. Embracing the strengths alongside the flaw of who we are is much more fulfilling than a one-dimensional niceness that has no vitality. Being “nice” is not the power of life. While we can’t escape the dark side of life, we can play out that dark side intelligently. The balance of light and dark is possible, bearable, and essential.

~

Until next time,

Sherry

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this essay, I recommend: What to Make of Remorse and Self-Blame

I recently published a collection of short writings about growing into oneself and becoming whole: Get “The Pluri Society” on Amazon.

That's beautiful work Sherry - again, I'm seeing wisdom of an old soul in your writing.

A couple of reflections... I had the rare luck of coming across the novels of Ursula Le Guin when I was about 12 years old. In the Earthsea trilogy, the main character lets loose his shadow and is then chased by it.... eventually he chases it across the Wall of Death...

I don't want to give away the ending as some might love to read this - I wouldn't say it was written with adults in mind... I understand that Ursula was a child psychologist who used stories to reveal ideas to kids...

To my inner Kid, these books pointed me at the need to integrate the Shadow... at an age where I was probably way too young to get the lifetime perspective on this... but the Idea remained.

And remains. Even today, in my morning practice, I'm contemplating shadow elements.... stuff I've worked on in therapy (which people might find helpful... hint is, there's a good chance that if you think you see your Shadow? You may have missed the point - it's IS the parts of you that you cannot see)..

... and there's an idea to play with there, which you can do without a therapist/practice etc... When someone asks you about Who You Are.... make a mental note.. whatever you reply will give you a starting point.... Whatever you say you ARE probably gives you some pointers to what you Aren't (your shadow).

Keep it up Sherry - your writing is something I look forward to.

Excellent piece! I once heard a Jungian describe the Shadow as the "dark side of the moon." Lots of good things can be hidden there, but also evil desires and all that too. I also like the idea of an alternate take of what we usually tell kids: "You can be anyone and do anything!" Quite an optimistic or even hopeful statement on the one hand, but also (dear goodness) a warning too. When we see people on the news we deem as evil, who knows how close we were to being such people ourselves. And who knows if we will become them later on in life? Sartre comes to mind here:)