I Know Why You're Sad

Your intellect is making your soul sick. Read this as fiction, not self-help.

Most of our problems can be boiled down to one cause: the loss of soul.

No, I won’t define the soul because defining it is part of the problem. Definitions are an intellectual enterprise, and the soul is something beyond that entirely. Besides, you already know what the soul is; you just never knew that you don’t need a definition of it to talk about it.

No one can tell you exactly how to live.

Religion prescribes, but even religion doesn’t give you the reasons for its prescriptions—that’s why it’s called faith.

Like a child who doesn’t understand why she has to sleep before 9 P.M. (and has to take the unsatisfactory answer of “because you’re still growing!”), we can’t comprehend why our soul needs holy vitamins. And we don’t need to.

These may sound like strictly Christian terms, but I am not proposing Christianity. I am showing you the religious sensibility that’s essential for the spiritual part of our lives to thrive.

Every psychological problem, at its root, is a religious problem. The mind takes the shape of a redemption story: we need a crisis, a patriarchy, a great mother, an underdog, and a sacrifice. Modern self-help canonizes slogans like “live every day like it’s your last” or “be the change you wish to see in the world” because the soul has an affinity for commandments.

Therapy can’t save you.

The loss of soul is the root cause of ineffective therapy and hollow self-help books. Bad therapy tries to be salvational: if only you were more patient, expressive, or capable of anger, your problems would be gone!

It’s why we falsely split people into “thinking” or “feeling” types, when in reality, people are both and more, all at the same time. To shrink the soul so it can be scientifically ranked on some psychometric test is to misunderstand spirituality—and human nature—entirely.

You can’t “think” your way to the soul. You also can’t “feel” your way to it. The soul is at the core of everything; when you neglect it, it doesn’t just go away, it turns to weird forms of obsession, addiction, and nihilism. It’s not something you grasp; it’s something that grasps you.

It’s why our qualitative experiences are treated mechanistically, like how screen time-limiting apps temporarily block your social media addiction without addressing the real reason for your anxiety, loneliness, or envy.

It’s the way we treat insecurities with surgery instead of reframing what we appreciate as beauty.

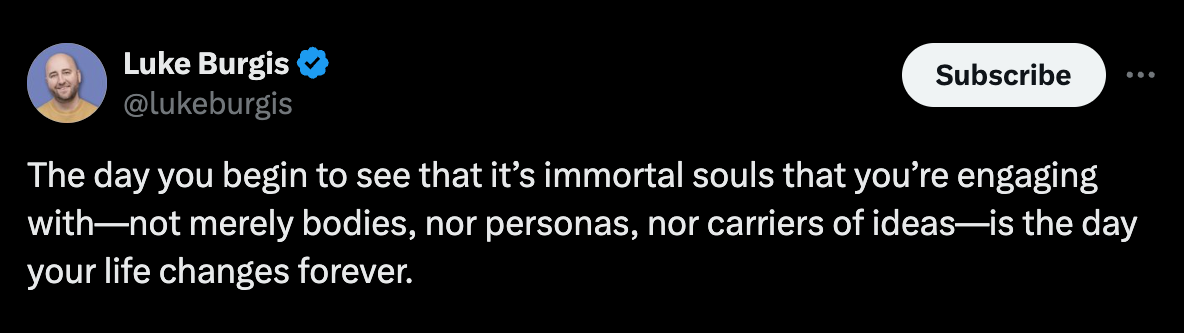

It’s ’s observation:

The word “psychology” roots in psyche, Greek for “soul”. It’s ambiguous whether it’s a science or an art. For most of history, it has been a mutation of philosophy, theology, or medicine. The Nazis actually played a role in professionalizing psychology when they recognized its serious potential in political strategy (i.e., propaganda). To this day, when I tell people that I majored in psychology, I receive mixed reactions ranging from “can you read minds?” to “did you learn manipulation?” to “are you a therapist?”

Frankly, I don’t care what it’s categorized as. What’s important is that it stays true to its original concern, which is about:

Caring for the soul.

I was in a mild existential crisis two Septembers ago.

I had the post-grad blues, and my “dream job” was far from what I had imagined it would be. My hair was falling out, I cried a lot, and worst of all, I was a size 6.

My best friend from college had moved back home to the other side of the country. We went from seeing each other every day to only seeing each other as avatars on a screen. And so, one week, I booked a spontaneous trip to Vancouver.

I landed around 9 P.M. and texted her, “I’m at the exit”. And when I looked up, I saw her standing by the automatic doors in that familiar forest green parka, blue jeans, and black leather boots. She had the brightest, ear-to-ear smile on her face, and my luggage suddenly felt lighter.

She said, “I’ve got a surprise for ya.”

I didn’t even care. I was just relieved to see her. When we got to her (dad’s) car, I found a half-dozen box of Lee’s Donuts waiting for me on the passenger seat and I felt tears well up behind my fatigue.

Through bites of salted caramel, memos of ‘my life lately’, and moments of silence as we cruised through the ancient conifers of Stanley Park, I learned that the soul is cared for—and cured—in that liminal space between understanding and dreaming.

Psychotherapy, as a secular science, focuses on consciousness. Know thyself, they say, figure out who you are, get to know your deepest self—what if that’s not what the soul asks of us? What if it needs mystery? (Related)

We have these rampant death-by-a-thousand-cuts type of problems, like procrastination, meaninglessness, and vague depression. We think we can take our life apart like an IKEA furniture, that the right job, relationship, or church is going to fix us.

I’m a fan of psychotherapy when it stays true to its original meaning—literally, soul-therapy. Like the Renaissance thinkers who reconciled medicine and magic or technology and ancient wisdom, we, too, should merge the religious contour of our nature with the quantifiable study of our mind.

I want you to be a little bit less conscious about the way you live. Let go. Have some faith. Make room for wit. For once, don’t think, don’t feel; just let things be. Consider this post fiction, not self-help.

Oh, and those are still the best donuts I have ever had.

Thanks for reading,

P.S. If this inspired you and you wish to talk about it, you can book a meeting with me here.