What I Think About When I Think About Nostalgia

Things we yearn for

The word “nostalgia” is made up of two Greek words: nostos, meaning “return”, and algos, “suffering”. So, nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased (or unappeasable) yearning to return.

A past that doesn’t exist anymore

There’s an old Vietnamese proverb that goes, “People say that time goes by; time says that the people go by.”

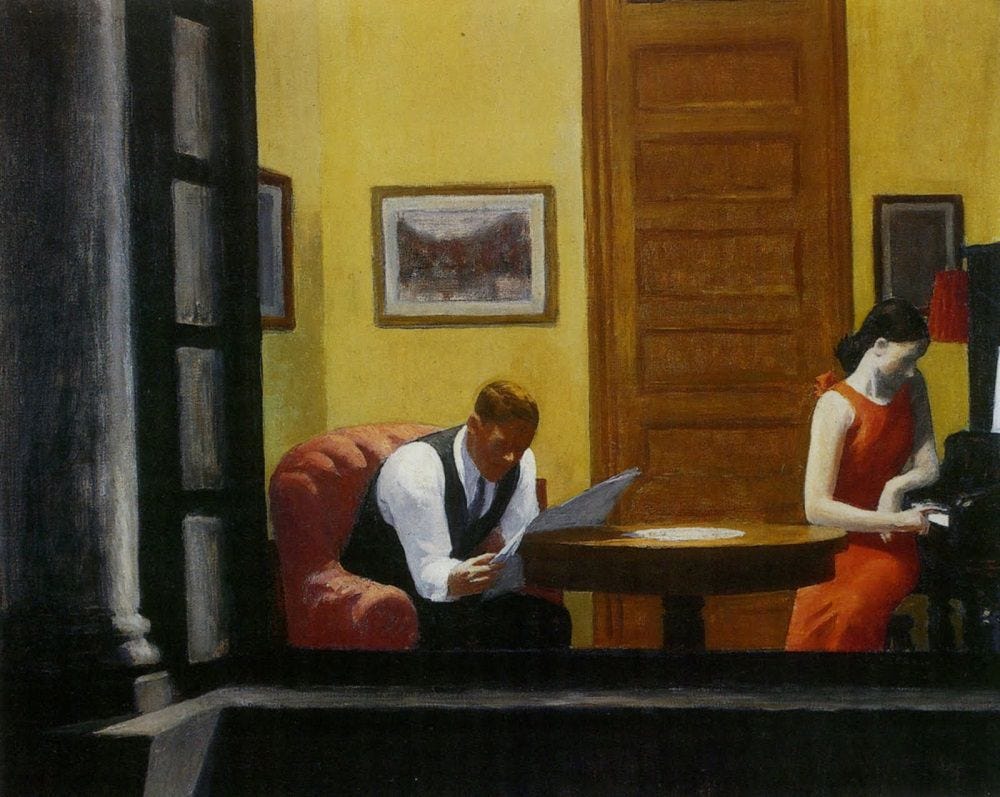

It’s not just a particular place or person that can make us nostalgic, it can also be a past version of the person or place. Saudade, for example, is Portuguese for the profound nostalgic longing for an absent beloved person or thing. There’s a particular type of sadness you feel when you catch up with someone you miss and realize that the version of them you were once friends with doesn’t exist anymore.

You won't ever find the same person twice, not even in the same person.

But, other times, with old friends who haven’t changed, reconnecting with them is one of the best feelings in the world. They bring out a part of …