“A Crown for Every Achievement.”

That’s Rolex’s slogan. Rolex is associated with the pinnacle of human performance. Rolex is all about the superlatives: Be the first. Be the best. Be the most. Be the fastest, strongest, and greatest.

The lore of Rolex exists in the “-est” suffix. Every model comes from a story of excellence:

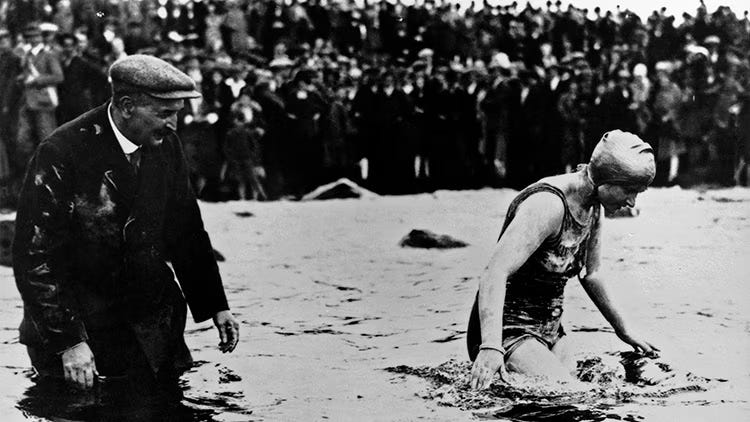

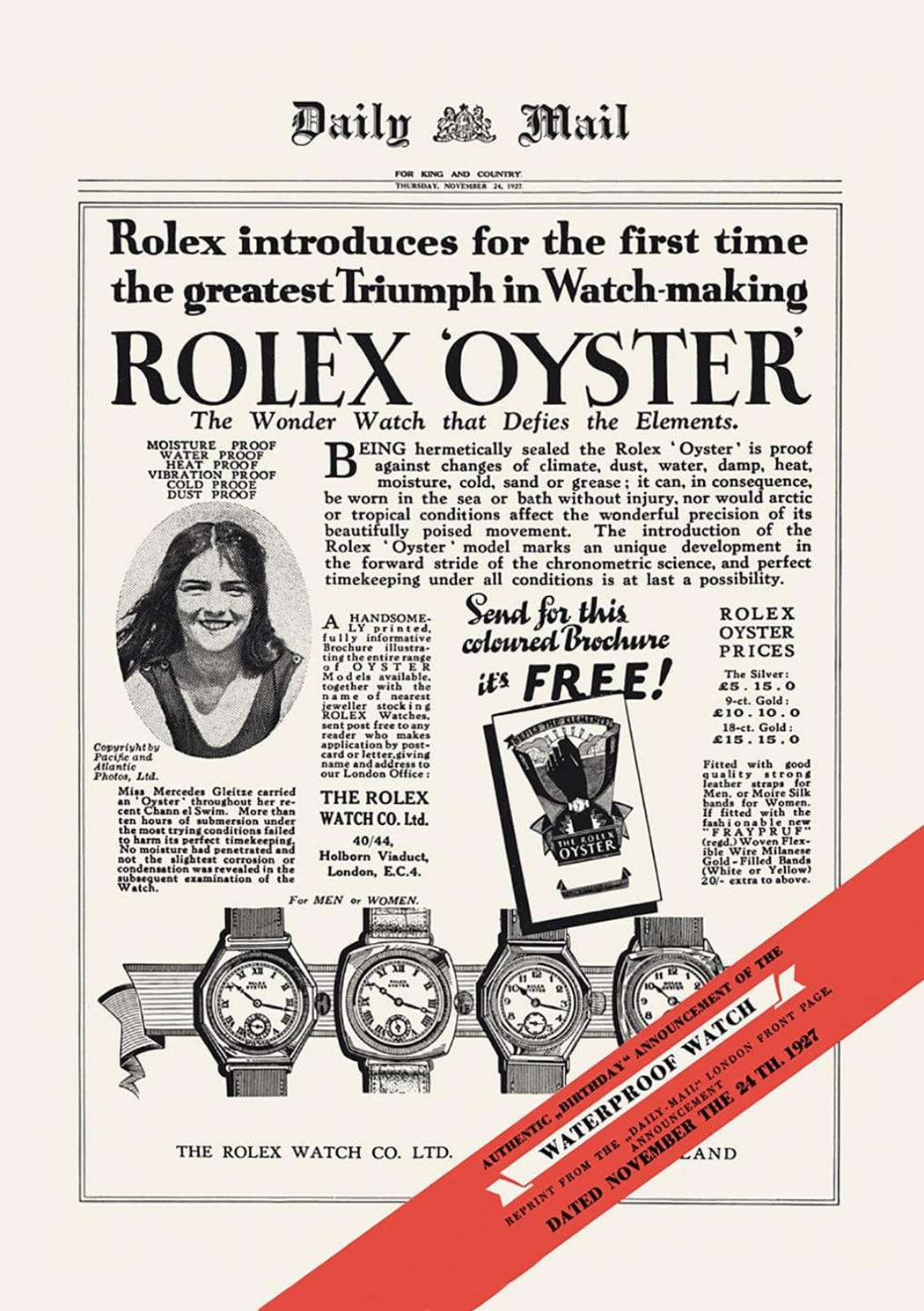

When Hans Wilsdorf, the company’s founder, heard that Mercedes Gleitze was going to break the world record by becoming the first British woman to swim from France to England, Rolex’s PR team sprained an ankle running to the shore of the English Channel with cameras, after requesting the athlete to wear the Oyster for the stunt.

The Oyster has since then cemented its reputation as being the world’s first waterproof wristwatch, flaunting its ability to function in freezing cold water.

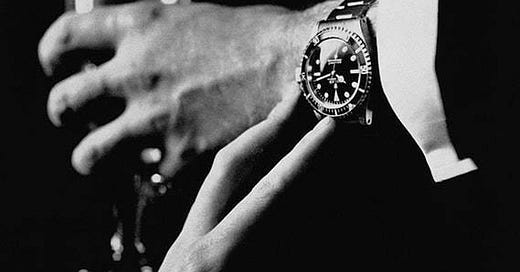

The Oyster gave rise to the Submariner—the first watch to be water-resistant up to 100 meters—and a new story was created: Designed for divers, it became associated with James Bond and has since signalled a certain ruggedness about the man who wears it: Mr. Submariner is dangerous yet refined with a taste for luxury, and he only dates femme fatales.

The Day-Date was the first watch to display both the date and the day of the week spelled out in full. It’s also known as the “President’s Watch” since it has been worn by numerous U.S. Presidents, making every man who puts one on before work feel like he has the most important job in the world.

When a man wears a Rolex, he wears its story:

He doesn’t need to be a world-class pilot to wear the GMT-Master; he’s just saying, “I’m well-travelled and I’ve got connections in every city.” He doesn’t need to have climbed Mount Everest to wear the Explorer; he’s saying, “I’m adventurous and cool.” Most Daytona wearers have no use for its tachymeter, but they wear it to say, “I’m better than you.”

“Our Story”

PR is just business-speak for storytelling.

Material is almost the same across brands: plasticky sunglasses from Zara, Jacquemus, and Linda Farrow are all made with the same cellulose acetate. Calf leather used by high-end ateliers is all supplied by French or Italian tanneries of similar standards and quality. Unless you’re a professional diver, the stainless steel of the Submariner is almost no different from that of the Seamaster (and the alloys of both are ultimately mined from the same planet).

Material has a limit. But the world isn’t just made out of material. Our experiences aren’t solely made out of what’s objective. There’s a pragmatic layer to reality and it’s the part of the world we can manipulate with mythologies, gossip, tradition, and fiction.

It’s why companies have “Our Story” on their website: we want to hear about the hero’s origin story, how you started from a garage or how it was your great-great-grandfather’s passion that you will forever protect from the grubby hands of private equity.

Stories give material meaning. Walt Disney once said, “People spend money when and where they feel good,” and people only feel anything when the story-shaped hole in their mind is met with a mythos, because being part of a plot gives material things a reason to be desired.

We want to be part of a legacy

Rolex isn’t just a watchmaker; Rolex is a master storyteller. Timepieces become little worlds with legends etched into every gear and dial. They become emblems of identity, status, and ambition. Rolex doesn’t say “Our Story”, they say “Perpetual - Our founding spirit”, because “Perpetual” isn’t just an automatic, self-winding rotor; perpetual also means ever-lasting.

Many refuse to wear logos because they don’t want to be walking billboards. But, above a certain price point, people start wanting the product to be identifiable. The clank of an Amex Platinum hitting the table; the interlocking CC’s on a Chanel; the rings on an Audi. That’s the definition of luxury: the product advertises the user.

Quiet luxury is no exception: the lack of logos is meant to advertise a certain “old-money” nonchalance about the person.

PR is about the manifesto behind the product. It’s invisible. It’s cultural. It’s imaginary (but not unreal). It’s about capturing the collective consciousness and massaging the cultural ache. Luxury is propped up by desires, but what makes a luxury brand last is when those desires turn into beliefs. It’s not just, “I want to wear this,” it’s, “I want to rest my faith and my identity on this brand.” People who wear Rolexes wear them because they want to be perceived as the kind of people who wear Rolexes (and maybe because they want to tell the time).

Storytelling turns wants into needs and preferences into philosophies.

The best things in life are free. The second best are very expensive.

—Chanel

Even when we know it’s kind of an illusion, we are happy to be part of it. Storytelling is powerful because it speaks to our dream of being part of something greater, to live out a story that makes us feel special, significant, and connected to a legacy.

People want to be part of an idea because ideas live forever. No one wants their identity to be limited to a trend or a fad. We consume things that make us feel like we are an active member in the history that is being made right now.

This is why brands that successfully weave a compelling story around their products or mission often find enduring devotion among their followers. Don’t just sell me a product—give me a shibboleth to signal my loyalty to others who are in the know, make me feel like I’m part of something exclusive, and offer me an invitation to join something eternal, something perpetual.

That’s it (for now). Thanks for reading,

![Vintage Ad] Suggestive Rolex Submariner Ad From The 70s : r/Watches Vintage Ad] Suggestive Rolex Submariner Ad From The 70s : r/Watches](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbcbc47ce-3b08-48b7-a8a5-d14a709f87e4_569x767.jpeg)

I’m reminded of a quote by Rory Sutherland:

“We don’t value things; we value their meaning. What they are is determined by the laws of physics, but what they mean is determined by the laws of psychology.”

The value of an object is not just the intrinsic utility that it provides, it is also the story that it tells us about ourselves. We buy narratives, not just objects.

“The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” —Muriel Rukeyser'